This article contains affiliate links.

It was no accident that Ron and Lona Pond’s blessing for Montana’s fallen Mann Gulch smokejumpers occurred on July 6. It was the same exact day 14 Hotshots fell to the South Canyon fire at Storm King Mountain in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, 28 years prior. The pair had given a similar blessing for the Colorado victims exactly a year before.

“It’s going to take a long time for many hotshots and smokejumpers to bring closure,” said Lona.

But the father-daughter team had another reason for their visit to the Smokejumper Visitor Center in Missoula, Montana, aside from their blessing ceremony—they want to raise awareness about the need for better pay and improved healthcare for wildland firefighters.

One Big Family

According to the National Interagency Fire Center, 90 interagency hotshot crews of 20 members each exist nationwide, with most crews located in the West.

About 450 smokejumpers are stationed at nine bases across the western United States, with 75 located in Montana and 165 working out of Idaho. These elite crews are deployed across the country as needed throughout the fire season, to work with other crews.

“We all know each other,” said Lona. “We’re family.”

Big Risks, Low Wages

One could easily argue that wages for the individuals risking their lives to save our wildlands are frightfully low, despite recent moves to raise the bar. In June of 2021, minimum wage for entry-level federal wildland firefighters was increased to $15 per hour.

At the state level, in January of this year, Montana Governor Greg Gianforte announced an increase in the base pay for Montana’s seasonal firefighters to a minimum of $15.50 per hour. According to state job listings, workers can make as much as $16.19 per hour. In March, Idaho Governor Brad Little signed legislation increasing hazard pay for wildland firefighters in his state. Starting pay in Idaho is $15 per hour.

These amounts are on par with employee wages at McDonald’s or Burger King.

In addition, because of the seasonal nature of the work, most wildland firefighters are not employed full time and, therefore, don’t qualify for health benefits.

Michele Hart is the wife of Tim Hart, a smokejumper out of West Yellowstone, Montana, who died June 2, 2021, after suffering injuries from a hard landing into a New Mexico wildfire. She is actively working with the organization Grassroots Wildland Firefighters to pass legislation that would improve pay and healthcare benefits for wildland firefighters, to prevent what they claim is an inevitable exodus of vital workers unwilling to tolerate poor working conditions in a career that’s only becoming more dangerous with the effects of climate change.

“These heroes endure brutal conditions. They sleep on the ground for weeks, work in smoke without the aid of respiratory protection, endure extreme physical and mental fatigue from 16-hour shifts, and combat dangerous conditions through a fire season dramatically extending with each passing year,” she wrote in an article for the January 2022 edition of Smokejumper magazine.

“To offset low wages and off-season bills, a pervasive incentive is created to work, no matter how physically drained or emotionally exhausted they become,” she continued. Hart said her family struggled financially, with her husband having to live three summers out of his truck while working fires in Idaho, because no affordable housing was available.

“Exacerbating these concerns is the mental strain and emotional toll caused by these brutal work conditions,” she continued.

Mental Strain

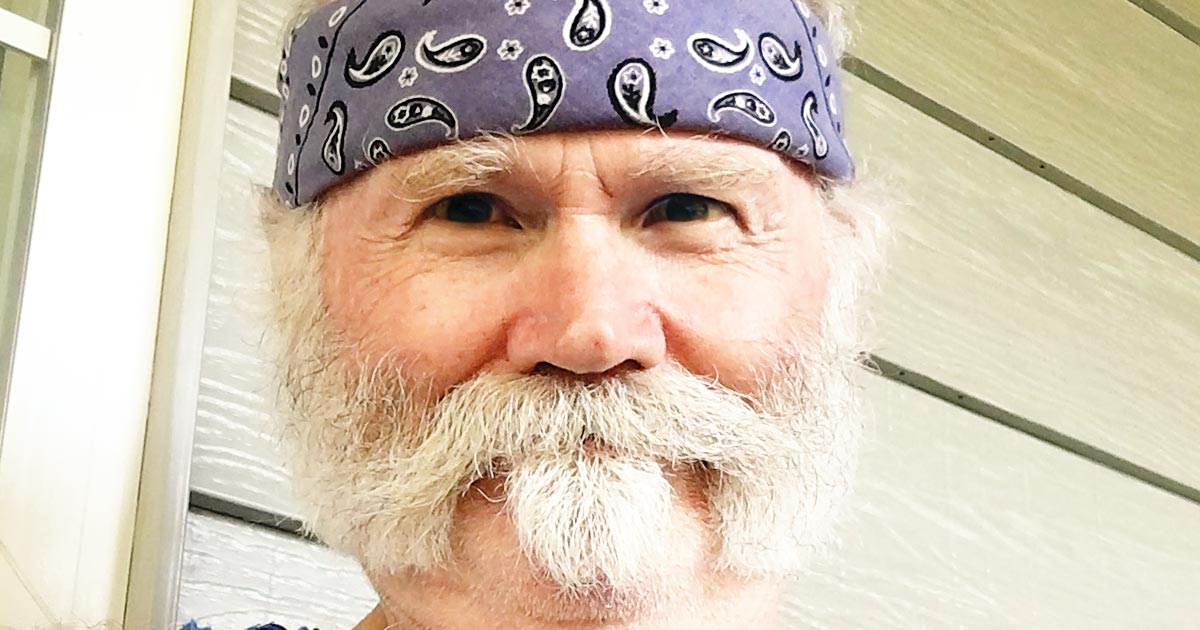

Tom Shepard, 71, of Moscow, Idaho, knows only too well about the mental strains to which wildland firefighters are subjected. He retired 19 years ago from the Prineville Interagency Hotshots (PIA) in Oregon and suffers from PTSD because of his experience in 1994, when he served as the Superintendent of the PIA during the ill-fated Colorado fire on the slopes of Storm King Mountain. Nine of the 14 casualties were from his own Prineville crew. He was emotionally devastated.

“As far as healing and recovery, it’s an interminable task, it seems like, to get back to where you want to be in your mind,” said Shepard in a 2016 interview for a Wildland Fire Safety Training video published by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. “It took 15 years for me before I went back, and I walked up that hill. I walked that west fireline. I didn’t know how I was going to react to that. Needless to say, it was an emotional time for me.”

For Love of Work

But despite the hardship, Shepard loved the work. In a phone interview, he spoke slowly and deliberately when discussing why anyone would want to risk their life for fast-food wages.

“If you love what you’re doing, you’re willing to put up with a little lower pay,” he said. “You’ve gotta have a passion for it, because you do put up with horrible working conditions.”

But he didn’t hesitate when it came to listing the benefits of the job.

“The opportunity to be outside in the forest or desert, to travel to different places, the feeling of accomplishment when you were able to have some success doing what you were doing,” he said. “And the adrenaline rush, of course. There’s just nothing that replaces that rush of excitement when you’re out there trying to beat mother nature at her own game.” ISI

For more information on the Grassroots Wildland Firefighters efforts to pass legislation that would improve pay and health benefits for wildland firefighters, visit grassrootswildlandfirefighters.com